1. Individual losses

C1 For the notion of individual losses, see Comment 2 to Article 5.2.

2. Paragraphs (1) and (2): Originating or original cause

C2 Under the PRICL, the unifying factor of “cause” allows for a broader aggregation than the unifying factor of “event”. Furthermore, in the PRICL, the concepts of “cause” and “source” are treated as equivalent. Thus, whenever a contract refers to the unifying factor of “source”, the parties agree on an aggregation pursuant to Article 5.3.

C3 An aggregating cause may give rise to multiple instances of materialized perils or acts, omissions or facts triggering liability, each of which may result in numerous losses. Under cause-based aggregation, any losses that arise from such a cause are aggregated, regardless of the number of instances a peril materialized or the number of acts, omissions or facts triggering liability.

C4 Similarly, the reinsured may take out reinsurance against multiple perils under a single contract. If a cause within the meaning of Article 5.3 leads to the materialization of multiple different perils reinsured against or multiple different acts, omissions or facts triggering liability, such cause is the unifying factor not only for any losses resulting from multiple instances of the materialization of the same peril or multiple identical acts, omissions or facts triggering liability, but also for losses resulting from the materialization of different perils or different acts, omissions or facts triggering liability.

Illustration

I1. Reinsured A takes out reinsurance against the perils of tsunami and fire. An earthquake occurs, provoking a tsunami and a fire independently of one another. Multiple losses result from the tsunami and multiple losses result from the fire.

The peril of tsunami materialized in one instance, as did the peril of fire. Within the meaning of Article 5.2(1), the materialization of the peril of tsunami is considered an event distinct from the materialization of the peril of fire. In the ordinary course of things, it appears quite likely that an earthquake will result in the materialization of a tsunami and the materialization of a fire. Under Article 5.3(1), the earthquake is, therefore, to be considered the unifying cause. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of either the fire or the tsunami are aggregated under paragraph (1).

C5 As illustrated, the concept of “cause” is much broader than the concept of “event”. In fact, a cause may be the reason why an event occurred. More specifically, a state of affairs (cf. Axa Reins (UK) Ltd v Field [1996] 1 WLR 1026, 1035), a state of ignorance (cf. Caudle v Sharp [1995] CLC 642 (CA) 649), a lack of proper training (cf. Countrywide Assured Group Plc v Marshall [2002] EWHC 2082 (Comm) [13] (Morison J)), a misunderstanding as to the results of discussions (cf. American Centennial Ins Co v INSCO Ltd [1996] WL 1093224, 8) and a failure to put in place an adequate system to protect goods (cf. Municipal Mutual Ins Ltd v Sea Ins Co Ltd [1998] CLC 957, 967) may be considered causes for the purpose of aggregating losses.

3. Causation

a. Causation in general

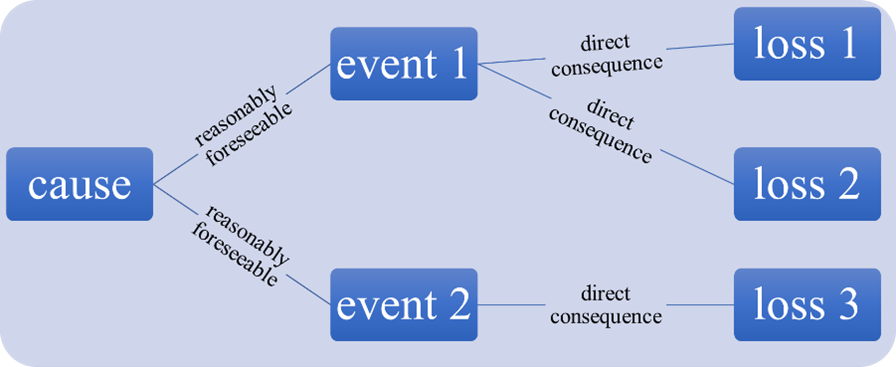

C6 There must be a causative link between the relevant cause on the one hand and any losses to be aggregated on the other hand. This involves a three-step analysis.

C7 First, any loss covered under the contract results from an instance of materialized peril reinsured against or an act, omission or fact triggering liability, i.e. an event within the meaning of Article 5.2. The relevant event or events as defined in Article 5.2 is/are to be determined and pinpointed in the chain of causation. For more details as to this test, see Comments 6 et seq. to Article 5.2.

C8 Second, to ascertain the aggregating cause as defined in Article 5.3, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation as compared to Article 5.2. It is to be determined whether there is a cause that triggered one or multiple events within the meaning of Article 5.2. If there is no such cause, the materialization of a peril reinsured against or the act, omission or fact triggering liability is to be considered the aggregating cause. In this case, an event within the meaning of Article 5.2 is equivalent to a cause within the meaning of Article 5.3.

C9 By contrast, if there is a cause in which one or multiple events (Article 5.2) originated, it is necessary to test whether it was reasonably foreseeable that such a cause would give rise to one or multiple such events. If so, this cause is to be considered the aggregating cause within the meaning of Article 5.3. It is distinct from one or multiple events within the meaning of Article 5.2. It is important not to give a court or arbitral tribunal the leeway to consider the materialization of a peril reinsured against or the act, omission or fact triggering liability as the relevant cause within the meaning of Article 5.3. Otherwise, the parties’ choice for a broader aggregation mechanism would be disregarded.

C10 Third, not every loss arising from an event, which in turn originates in such an aggregating cause, may be aggregated. Rather, the only losses that are aggregated are those that can be said to arise as a direct consequence of the materialization of the peril reinsured against or the act, omission or fact triggering liability.

Consequently, the standard of “reasonable foreseeability” operates between the aggregating cause within the meaning of Article 5.3 and the materialization of a peril reinsured against or an act, omission or fact triggering liability, i.e. an event within the meaning of Article 5.2. By contrast, the standard of “direct consequence” operates between an event within the meaning of

Article 5.2 and the individual losses. This is illustrated below.

Figure 1: Operation of the standards of reasonable foreseeability and direct consequence

b. Reasonable foreseeability

C11 A cause may be somewhere further back in the chain of causation than an event. The concept of reasonable foreseeability is meant to restrict how much further back in the chain of causation a court or arbitral tribunal may look in search of an aggregating cause. In fact, not every cause that gives rise to an instance of materialized peril can be considered an aggregating cause within the meaning of Article 5.3. If a cause is too loosely connected to the event to justify an aggregation of losses, it cannot be considered an aggregating cause within the meaning of Article 5.3.

C12 Under Article 5.3, a cause may be considered the unifying factor for the purpose of aggregating losses if it was reasonably foreseeable to the parties that – in the ordinary course of things – a cause of this kind could lead to an event of the type under consideration, i.e. an instance of materialized peril (Article 5.2(1)) or an act, omission or fact that triggers the primary insured’s liability (Article 5.2(2)).

C13 Consequently, it need not be reasonably foreseeable that a cause would give rise to multiple events or that such events would eventually result in multiple losses. Similarly, the number of separate losses that may arise from an event originating in the cause in question or the extent of such losses does not have to be reasonably foreseeable. Rather, it is sufficient that it is reasonably foreseeable that a cause of the kind in question may lead to an event of the kind in question.

C14 The requirement of reasonable foreseeability is an objective one. Whether a particular cause was reasonably foreseeable must be determined by reference to a reasonable person in the position of the parties. Furthermore, reasonable parties assess the standard of foreseeability in light of the ordinary course of things.

C15 It is at the time of entering into the contract that reasonable parties must have been able to reasonably foresee that a cause of the kind in question might result in one or more reinsured events.

C16 In any case, it is important to note that the concept of foreseeability in Article 5.3 does not correspond with the concept of foreseeability in tort law or the concept of foreseeability in general contract law or insurance law (cf. Swisher (2002) 361 et seq. for the distinction between the different concepts).

C17 In fact, in tort law, the concept of foreseeability is used to determine “whether [someone’s] act, or omission to act, was too remote or did in fact constitute the proximate cause” of the injured’s damage and therefore triggered the wrongdoer’s liability (Swisher (2007) 9). In general contract law, the concept of foreseeability is used to limit a party’s liability for breach of contract (§ 351(1) Restatement (Second) of Contracts). In insurance law, the concept of foreseeability is used to determine whether a certain loss is covered by the insurance policy (cf. Swisher (2002) 361 et seq.). In all of these cases, the concept of foreseeability is used to limit liability.

C18 The PRICL does not use the concept of reasonable foreseeability to limit the reinsurers’ liability, i.e. to determine whether a certain loss is covered under the contract. Rather, the question of whether these separate losses are to be aggregated only arises once it has been established that multiple losses are generally covered by the contract. In fact, limiting the extent of aggregation can – depending on both the structure of the reinsurance policy and the structure of the individual losses – lead to an increase or decrease in a reinsurer’s liability.

Illustrations

I2. Under the primary insurance policy, Reinsured A provides professional liability insurance to Primary Insured C. Primary Insured C is an insurance underwriter who underwrites a number of insurance contracts without appreciating the risk of asbestosis. Reinsurer B provides reinsurance coverage to Reinsured A for the third-party liability insurance policy between Reinsured A and Primary Insured C.

It must be determined whether, at the time of contract formation, it was reasonably foreseeable in the ordinary course of events that an underwriter’s liability would be triggered by underwriting insurance contracts without having assessed all of the known risks.

The risk of asbestosis was public knowledge at the time Primary Insured C underwrote the insurance contracts. It may therefore be said that it was reasonably foreseeable that an underwriter’s ignorance about this risk would lead to an act of negligent underwriting. Consequently, the underwriter’s ignorance is to be considered a cause within the meaning of Article 5.3. This is so because – in the ordinary course of things – it appears reasonable that the failure to account for such a significant risk as asbestosis could trigger Primary Insured C’s liability. Therefore, under paragraph (2), any losses that originated in Primary Insured C’s ignorance are to be aggregated.

I3. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for banks against the peril of damage or theft. Over the course of five months, multiple instances of robbery occur independently of one another. Sociological experts have opined that these instances of theft could be considered indicative of the increasing materialism in society.

The peril “theft” materialized in several instances. Each instance of materialization is to be considered a distinct event for the purpose of Article 5.2(1). From the perspective of reasonable parties to a contract reinsuring property risks, it does not appear reasonably foreseeable in the ordinary course of things that separate instances of theft would occur due to such a general trend as increasing materialism in society. For lack of reasonable foreseeability, increasing materialism in society cannot be considered a unifying cause under Article 5.3(1).

C19 Like the concept of proximity (cf. Comments 21 et seq. to Article 5.1), the concept of reasonable foreseeability is generally open to result-oriented judgments and may therefore be considered somewhat indeterminate. In full awareness of this fact, the standard of reasonable foreseeability is adopted in Article 5.3, a standard which may – under certain circumstances – not be clear-cut, but nevertheless serve to reduce legal uncertainty to some degree.

c. Direct consequence

C20 It is not appropriate to aggregate every loss that arises from the same event which itself originates in a cause within the meaning of Article 5.3. Rather, the only losses that are to be aggregated are those that are a direct consequence of the relevant event, i.e. an instance of materialized peril reinsured against or an act, omission or fact triggering liability.

C21 Therefore, the necessary test is whether an individual loss can be considered a direct consequence of the relevant event within the meaning of Article 5.2. In order to ensure this, as under Article 5.2, only the strength of the causal link between the instances of materialized perils or acts, omissions or facts triggering liability on the one hand and the corresponding losses on the other hand are to be examined. For the test of whether a loss can be said to be a direct consequence of an instance of materialized peril, see Comments 16 et seq. to Article 5.2.

C22 By contrast, the “direct consequence” test does not involve determining the degree of causation between the aggregating cause within the meaning of Article 5.3 and the individual losses.

Illustrations

I4. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for a large number of buildings against the peril of tsunami, with the peril of earthquake excluded. An earthquake occurs, triggering multiple separate tsunamis, each of which damages some buildings.

The peril of tsunami materializes in several instances, each constituting a distinct event for the purposes of Article 5.2(1). Having identified multiple tsunami events, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that provoked each of the tsunamis. In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that an earthquake may result in a tsunami. Under Article 5.3(1), the earthquake is, therefore, to be considered the unifying cause. The fact that the peril of earthquake is excluded from the coverage under the contract does not prevent the earthquake from serving as the aggregating cause under paragraph (1).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective tsunami. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of the tsunamis are aggregated under paragraph (1).

I5. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for a large number of supermarket stores against the peril of damage or destruction by vandalism. After the country’s president resigns, 22 stores are damaged by rioters in multiple acts of vandalism over a period of some two days. The rioters are reportedly centrally orchestrated by the government. Having determined that the numerous acts of vandalism constitute multiple events, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of the acts. In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that centrally orchestrated political rioting could lead to one or more acts of vandalism. Under paragraph (1), the rioters’ centralized orchestration is, therefore, to be considered the aggregating cause.

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective act of vandalism. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of the acts of vandalism are aggregated under paragraph (1) (facts based on Mann v Lexington Ins Co [2000] CLC 1409 which, by contrast, dealt with event-based aggregation).

I6. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for a large number of supermarket stores against the peril of damage or destruction by vandalism. Following a substantial increase in the market price of cigarettes, 22 stores are damaged in multiple, independent acts of vandalism over a period of some two days. A majority of rioters state that they vandalized the stores due to the price increase. Having determined that the numerous acts of vandalism constitute multiple events, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of the acts.

In the ordinary course of things, it does not appear reasonably foreseeable that an increase in the cigarette prices would lead to one or more instances of vandalism. For lack of reasonable foreseeability, the prices increase cannot be considered a unifying cause under paragraph (1).

I7. Reinsured A provides professional indemnity insurance to a managing agent of a syndicate at Lloyd’s. Due to culpable misappreciation, the agent repeatedly fails to pay sufficient regard to proper principles of underwriting. After incurring substantial losses, the members of the syndicate bring an action in negligence against the managing agent.

With each act of underwriting in disregard of the “proper principles of underwriting”, the liability of the managing agent is triggered. Hence, each act of underwriting constitutes a separate event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each act of underwriting constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these underwritings. It appears reasonably foreseeable that an underwriter who is unaware of proper underwriting principles could negligently underwrite contracts and thereby incur liability. Consequently, the agent’s culpable misappreciation can be said to constitute the single originating cause of all the negligent acts and can, hence, be considered a common cause for the purposes of Article 5.3(2).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective act of underwriting. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of the acts of underwriting are aggregated under paragraph (2) (facts based on Cox v Bankside Members Agency Ltd [1995] CLC 180 (QB)).

I8. Reinsured A issues a policy of insurance covering the liabilities of 14 directors, officers and employees of an American financial institution. The institution collapses and a claim is made against all 14 of the directors and officers, each of whom is alleged to be personally liable for negligence or other fault in the handling of the institution’s affairs. Any faults committed by the directors and officers can be said to be the consequence of a common culpable misunderstanding, as the result of a discussion between them, on which they all subsequently acted.

Each negligent act or fault triggers the respective D&O liability. Thus, each negligent act or fault can be considered a separate event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each act constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these acts. It appears reasonably foreseeable that directors and officers may reach a common understanding that may translate into multiple wrongful acts and omissions. Hence, their discussion that resulted in the misunderstandings can be regarded as the common cause for the purposes of Article 5.3(2).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective act. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of the acts are aggregated under paragraph (2) (facts based on American Centennial Ins Co v INSCO Ltd [1996] WL 1093224).

I9. Reinsured A provides liability insurance to a port. Equipment stored at the port is vandalized through a series of individual acts of pilferage. The owner of the equipment brings an action against the port for not putting in place an adequate system to protect the goods from pilferage and vandalism.

The port’s liability is triggered by each act of vandalism it is unable to avert. Thus, each instance of vandalism the port was unable to avert can be considered a separate event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each act constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these omissions to avert acts of vandalism. The port’s inability to avert these instances of vandalism originated in its failure to put in place an adequate system of protection from pilferage and vandalism. It appears reasonably foreseeable that stored goods may be vandalized where no such system of protection is put in place. Consequently, the port’s failure can be regarded as a common cause for the purposes of Article 5.3(2).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective omission to avert acts of vandalism. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of these omissions are aggregated under paragraph (2) (facts based on Municipal Mutual Ins Ltd v Sea Ins Co Ltd [1998] CLC 957, 966 et seq.).

I10. Reinsured A provides professional indemnity insurance to Primary Insured C – an insurance company. Several of Primary Insured C’s underwriters mis-sell pensions for which they are held liable. They are found to have done so due to their lack of proper training.

Primary Insured C’s liability is triggered by each instance of mis-selling a pension. Therefore, each instance of mis-selling can be considered a separate event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each act of mis-selling constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these instances of mis-selling. It appears reasonably foreseeable that not providing the sales personnel with adequate training could lead to the mis-selling of pensions. Therefore, the lack of proper training can be considered a common cause for the purposes of Article 5.3(2).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective instance of mis-selling. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of these instances of mis-selling are to be aggregated under paragraph (2) (facts based on Countrywide Assured Group Plc v Marshall [2002] EWHC 2082 (Comm) [13] (Morison J)).

I11. Reinsured A provides professional indemnity insurance to Primary Insured C, a chemical manufacturer that has operated in locations throughout the US since the early 1900s. In the 1980s, federal, state and local governments as well as a number of private parties commenced environmental actions directed at more than 150 of the manufacturer’s plant and disposal sites throughout the country. Experts have found that the pollution originated in the manufacturer’s deficient corporate environmental policy.

Primary Insured C’s liability is triggered by each act of pollution. Therefore, each instance of pollution can be considered a separate event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each instance of pollution constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these instances of pollution. It appears reasonably foreseeable that not having in place an adequate corporate environmental policy could lead to the pollution of environmental sites. Therefore, the lack of a proper environmental policy can be considered a common cause for the purposes of Article 5.3(2).

The final step is to determine whether each loss can be considered a direct consequence of the respective instance of pollution. Any losses that can be considered a direct consequence of any of these instances of pollution are to be aggregated under paragraph (2) (facts based on Travelers Cas and Sur Co v Certain Underwriters at Lloyd’s of London, 96 NY2d 583 (NY 2001)).

4. Sublimits

C23 Contracts of reinsurance typically include not only coverage limits but also sublimits. A sublimit defines a limit of liability for a particular peril when the contract provides for coverage against a multitude of perils; for a specific reinsured asset where reinsurance is taken out for a range of different assets; or for a specific location where the reinsured assets are located at multiple sites.

C24 Under the PRICL, aggregation is dealt with on each level of limits, i.e. total coverage limits and sublimits. The aggregation mechanism does not have to be identical on each level of limits.

Illustrations

I12. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for a large number of buildings on an island against the perils of fire and tsunami. The contract provides for a total liability limit of USD 30 million for any losses originating in one cause. It further provides for sublimits of USD 20 million for losses arising from the peril of tsunami and USD 20 million for losses resulting from the peril of fire. An earthquake provokes a tsunami which hits the island’s coast, causing losses in the amount of USD 20 million. At the same time, it gives rise to a short circuit resulting in a fire which causes a loss totalling USD 30 million.

Two separate perils (tsunami and fire) materialize. Each materialization is to be considered a distinct event within the meaning of Article 5.2(1). The sublimits clause refers to the materialization of a peril reinsured against. Thus, for the purpose of aggregation under the sublimits, an event-based aggregation according to Article 5.2(1) applies. The tsunami losses of USD 20 million remain within the sublimit for tsunami losses. The fire losses of USD 30 million, however, exceed the sublimit for fire losses by USD 10 million. Hence, USD 10 million of the fire losses are not covered under the contract.

All the losses covered under the sublimits may then be aggregated under the total liability clause providing for a cause-based aggregation. Both fire losses and tsunami losses are caused by the earthquake. Therefore, the earthquake can be considered the unifying cause under Article 5.3(1). Consequently, USD 20 million of tsunami losses are aggregated with USD 20 million (not USD 30 million) of fire losses. The aggregate of these losses amounts to USD 40 million, which exceeds the total liability limit by USD 10 million. Under this contract, USD 30 million of losses resulting from the unifying cause of earthquake are covered.

C25 If the sublimits clause provides for a sublimit with regard to the losses that occur to a specified reinsured asset and originated in one cause, then the parties agreed on cause-based aggregation for losses occurring to this asset and paragraph (1) applies. Any losses covered with regard to this asset are then aggregated with other losses under the total limit of liability clause if they originated in the same cause.

Illustration

I13. Reinsured A takes out property reinsurance for a large number of buildings on an island against the perils of tsunami and fire. The contract provides for a total liability limit of USD 60 million for any losses originating in one cause. It further provides for a sublimit of USD 20 million for damage that occurs to Building X at the sea bank. An earthquake provokes a tsunami which hits the island’s coast, causing losses amounting to USD 30 million. Furthermore, it causes tsunami losses in the amount of USD 15 million as well as a fire loss of USD 10 million to Building X.

Two separate perils (fire and tsunami) materialize independently of one another. Each instance of materialization is to be considered a distinct event within the meaning of Article 5.2(1). The sublimits clause refers to damage occurring to Building X and originating in one cause. Thus, for the purpose of aggregation under the sublimits, a cause-based aggregation according to Article 5.3(1) applies. Both the tsunami loss and the fire loss to Building X originated in the earthquake and therefore aggregate. This aggregate amounts to USD 25 million and exceeds the sublimit with regard to Building X by USD 5 million. Hence, USD 5 million of losses to Building X are not covered under the contract.

All the losses covered under the sublimit may then be aggregated with other losses under the total liability clause providing for a cause-based aggregation. Both losses to Building X and other losses are caused by the earthquake. Therefore, the earthquake can be considered the unifying cause under paragraph (1) with regard to the total limit of liability. Consequently, USD 30 million for further losses are aggregated with USD 20 million (not USD 25 million) for losses occurring to Building X. The aggregate of these losses amounts to USD 50 million and is within the total liability limit of USD 60 million. Under this contract, USD 50 million of losses resulting from the unifying cause of earthquake are covered.

5. Treaty reinsurance

C26 In the case of treaty reinsurance, a reinsured takes out reinsurance for a multitude of risks covered by multiple primary insurance policies (the portfolio) under a single contract.

C27 A common cause may lead to one or more instances of materialized peril (Article 5.2(1)) or multiple acts, omissions or facts triggering liability (Article 5.2(2)), which in turn trigger a multitude of primary insurance policies within the portfolio. Under Article 5.3, these losses are treated as one single loss with regard to reinsurance deductible and coverage limit.

Illustrations

I14. Reinsured A takes out reinsurance for a portfolio of property insurance policies. The peril insured against is fire. An earthquake occurs, leading to 15 separate fires at different places. These separate fires cause damage to properties that are insured under multiple primary insurance policies, all forming part of the treaty reinsurance portfolio. The peril of fire materializes in 15 separate instances.

Each instance of materialization is to be considered a distinct event within the meaning of Article 5.2(1). In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that an earthquake could result in a fire. Therefore, under Article 5.3(1), the earthquake is to be considered the aggregating cause. Consequently, any losses occurring as a direct consequence of any fires that originated in the earthquake are to be aggregated. The fact that the separate fire losses occurred under separate primary insurance policies does not preclude the aggregation of losses under paragraph (1).

I15. Reinsured A takes out reinsurance for a portfolio of property car insurance policies. The peril insured against is damage or destruction. Due to an instance of heavy rainfalls in Germany, multiple accidents occur independently of one another.

The peril of damage or destruction materializes in multiple instances. Each instance of materialization is to be considered a distinct event for the purposes of Article 5.2(1). In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that heavy rainfalls could lead to the occurrence of a car accident, resulting in damage to or destruction of a car. Therefore, under Article 5.3(1), the rainfalls are to be considered the unifying cause. Consequently, any losses that occurred as a direct consequence of any accident originating in the heavy rainfalls are to be aggregated. The fact that the separate losses occurred under separate primary insurance policies does not preclude the aggregation of losses under paragraph (1).

I16. Reinsured A takes out reinsurance for a portfolio of property car insurance policies. The peril insured against is damage or destruction. Due to multiple instances of heavy rainfalls in Germany and Argentina, multiple accidents occur independently of one another.

The peril of damage or destruction materializes in multiple instances. Each instance of materialization is to be considered a distinct event for the purposes of Article 5.2(1). In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that heavy rainfalls could lead to the occurrence of a car accident, resulting in damage to or destruction of a car.

Under Article 5.3(1), the rainfalls in Germany and the rainfalls in Argentina are each to be considered a separate unifying cause. Consequently, any of the individual losses resulting from the rainfalls in Germany are to be aggregated, and any losses arising from the rainfalls in Argentina are to be aggregated.

By contrast, as the rainfalls in Germany and those in Argentina are to be considered separate unifying causes under paragraph (1), the losses arising from the rainfalls in Germany are not to be aggregated with the losses resulting from the rainfalls in Argentina.

I17. Employees D, E and F, all work for the same employer, Primary Insured C, who has taken out three separate professional indemnity insurance policies for its employees. Reinsured A takes out reinsurance for all three primary insurance policies under one contract. For lack of proper training, Employees D, E and F independently of one another, trigger their liability by mis-selling pensions.

Each instance of mis-selling is to be considered a distinct event within the meaning of Article 5.2(2). Having determined that each act of mis-selling constitutes a separate event, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of these underwritings. In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that improper sales training could lead to the mis-selling of pensions. Therefore, under Article 5.3(2), the employees’ lack of training is to be considered the unifying common cause.

Any losses that occurred as a direct consequence of any of the acts of mis-selling are to be aggregated. The fact that the errors and omissions of each employee were insured under separate primary insurance policies does not preclude the aggregation of all the losses under paragraph (2) (facts based on Countrywide Assured Group Plc v Marshall [2002] EWHC 2082 (Comm) [13] (Morison J)).

6. Life insurance policies

C28 For the relevance of aggregating losses in life insurance, see Comments 30 et seq. to Article 5.2.

7. Bundled insurance products

C29 If a primary insurance policy contains aspects of first- and third-party insurance, it may be that an instance of materialized peril (first-party) and an act, omission or fact triggering liability (third-party) originated in the same cause. In such cases, losses under the first-party insurance are to be aggregated with losses under the third-party insurance.

Illustration

I18. A sole household insurance policy protects Primary Insured C against first- and third-party losses. Following a house party, Primary Insured C – while intoxicated – damages an expensive work of art that was displayed at the party. By negligently damaging the painting, Primary Insured C triggers his liability under the third-party aspect of the household insurance. This accident can be considered the event for the purposes of Article 5.2(2). A few minutes later, Primary Insured C stumbles over his TV and damages it. Under the first-party aspect of the household insurance, the peril of damage by accident materialized when Primary Insured C stumbled over his TV. This accident can be said to be the event for the purposes of Article 5.2(1). Having determined that the damaging of the work of art and the damaging of the TV are to be considered two separate events, it is necessary to look further back in the chain of causation in search of an aggregating cause that gave rise to each of the events.

In the ordinary course of things, it appears reasonably foreseeable that an inebriated person may cause damage to goods belonging to himself or others through by uncontrolled movement. Therefore, under Article 5.3, Primary Insured C’s intoxicated state is to be regarded as the aggregating cause. The loss associated with the artwork and the loss associated with the TV are aggregated.